On Tools, Mimicry, and the Disappearance of Struggle

I was actually preparing another blog post, a transcription of a talk I gave recently about AI and semantics, but I’m hijacking my own plan because something’s been following me around all day, and I need to get it out of my system. It’s 3 PM on Tuesday. I just got back from class. So here goes.

As many of you might have seen, Google I/O just announced its new video generation model. Essentially, it's a series of photo-realistic rendered people that can talk, and the big deal here is that these videos come with sound that perfectly matches what you see on the screen. For the first time, we’re being promised high-fidelity video and audio generation that aligns frame-by-frame with a generated scene. We are also promised digital people saying the woodchuck thing repeatedly.

Whenever something like this comes out, of course I’m interested in the technology. But I’m always, perhaps more so, interested in the reception: how people respond. And what I saw depended heavily on where I looked. Last night at 1 AM, I was reading the replies under Google’s post on X (Twitter), and they were overwhelmingly positive. People were saying this is amazing. that we’ve come a long way in under two years since that weird Will Smith eating spaghetti video.

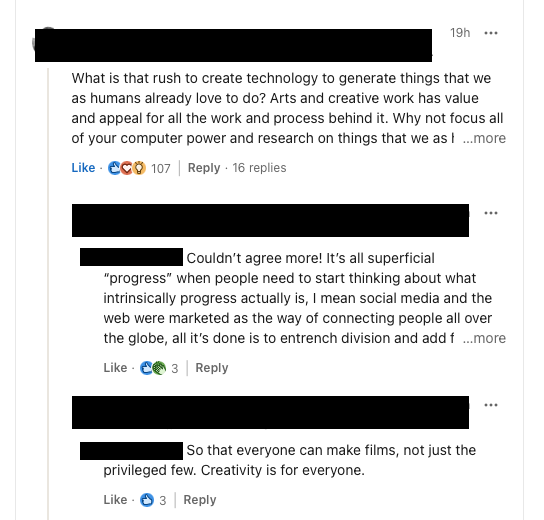

But this is where the praise seems to end. Everywhere else, the comments have been more skeptical—if not outright negative. One in particular on Instagram stuck with me. Someone wrote, “I fundamentally do not understand our need to replace humans.” That line stayed in my head, because the contrast between the enthusiastic comments from last night and the critical ones today isn't just a matter of tone. It reveals different conceptions of what "human" means.

To oversimplify: the first camp, the enthusiasts, see this as a tool of empowerment. For them, this is about access and possibility. “I’ve always wanted to be a filmmaker, but I had no budget. Now I can bypass the whole production line: no crews, no post-editing, no sound design.” It’s about compression. A shortening of distance between intention and execution. They value it because it collapses barriers and democratizes creation.

And I get it. I really, honestly, 100% do. But I see a fundamental error in this logic.

I think back to myself ten years ago. I was in university, and we had to produce short films. I don’t want this to sound like a humblebrag, but one of the short films I directed at the time, made with an iPhone and minimal means, actually received international recognition and awards. To this day, I think it’s one of the most ingenious things I’ve made. Not because I didn’t have actors or sound designers but because I had to think through the lack. The absence of resources shaped the creative form.

What I did back then was I translated the movie Cast Away into a story about urban homelessness. Not because I had some genius metaphor in mind about islands and cities, but because I was in my friend’s downtown apartment with no resources and a ticking clock. The story emerged from the constraint. The narrative emerged not from vision, but from necessity.

If I had had access back then to tools that allowed me to "perform professionalism," I’m sure I would’ve tried to mimic the kinds of films I admired—probably, if not absolutely certainly, poorly. The result would’ve been fast, polished, and hollow. It would’ve looked like everything else, and maybe I would’ve felt proud that it was “mine,” but it wouldn’t really have been. There wouldn’t have been time for the idea to ferment, to transform through my own process. I would have produced something made to be admired. And maybe even loved. But not something that mattered.

Risking staying disproportionately longer on the criticism of the first kind of reaction, I just want to say that this is also something you can notice in seasoned directors as well. And obviously, this is a matter of personal taste, but it’s not rare to hear that a director’s early works were groundbreaking—astonishing, thought-provoking—but then, as they became famous and gained access to more resources and bigger budgets, their films started to either become caricatures of themselves or lose that personal touch, that personal gaze. And I think that makes sense. You grow up admiring things and aspiring to become what you admire, and once you get the chance, the slope toward mimicry is super slippery. It seems like no one is immune to that (except, perhaps, from Andrei Tarkovsky)*.

Now let’s look at the skeptics. A lot of the criticism comes from people defending the time, effort, and labor it takes to make something. And I want to play devil’s advocate here: what makes something human? Is it the fact that it’s a product of struggle or strife? Is everything that emerges from hardship, by default, more human?

For a long time, I believed that. Up until recently, actually. This is something I had to unlearn in Silicon Valley. I came in with the dogma that the only things worth anything were the ones that hurt to make. If I didn’t suffer, it wasn’t good. If I didn’t doubt myself, it wasn’t real. And I don’t mean just in art—I mean with spreadsheets too. I would sit down and manually write the formulas I needed instead of just googling "how to do X in spreadsheets /reddit" and be done with it.

My instinct, even with Excel, was to build every formula from scratch. I resisted automation because I believed that effort equaled value. But Silicon Valley, the land of opportunity and optimization, taught me, slowly and painfully, that I was hurting my own creative process. Learning what to automate and what to preserve is how you design your capacity as a thinker and a doer. It’s how you scale your own imagination.

This, of course, edges us toward the rhetoric that frames generative video models as tools. And that’s where my discomfort begins. Because I don’t think these are tools. Or rather, I think we need to sit down and agree, collectively ideally, on what we mean when we say “tool.” To me, a tool is just one part of the process. It belongs within a process. It should be proportionate to it. When the tool grows large enough to become the entire process, when it swallows it whole, then either our idea of “tool” needs to change, or our idea of “process” does.

Last but not least, I think the name "Veo" is brilliant. It signals "we will take any sort of identity away from vIDeo so to start thinking about what it means to claim authorship of something created".

Or they simply took the personal away for ever. Who knows. We live in a dystopia and, as a student of mine brilliantly put it yesterday, no one has told us yet.

PS: God bless you Bong Joon Ho for bringing Scorcezze's teaching to the light. Also, did Parasite kill Mickey 17?

*Tarkovsky persuaded the USSR to get proper funding for Ivan's Childhood (1962) with a 250,000 rubles budget, proceeded to get 1.3 million rubles to make Andrei Rublev (1966) because of course and then gave birth to Solaris (1972), Mrror (1975) and Stalker (1979) with each less than 1million rubles. All of them masterpieces.